Artist in

Residence

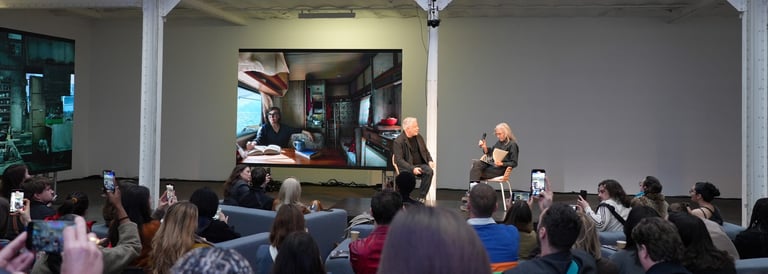

IKEA + Annie Leibovitz – Life at Home

Exploring the realities of home life through the lens of American photographer, Annie Leibovitz.

The IKEA Life at Home Report explores how people live today and how we can help make life at home better. In 2023, during Annie Leibovitz’s tenure as IKEA Artist in Residence, she travelled around the world, photographing people in their homes in seven different countries: Japan, the United States, Germany, Italy, India, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

The collaboration produced a series of 25 portraits that showed the nuances of life at home, and was showcased at a special event in Paris in February, 2024.