Alone together: Nesting

Writer Susie and IT consultant Jerome separated in 2021 after 18 years together. They have kept the family home in north London where their children aged 16, 15 and 11 live. Now they each spend alternate weeks in the family home. They also share a local bedsit where they spend the other nights alone.

‘Nesting’ is when parents going through a divorce opt to continue to share the same space for the benefit of the children. The adults move in and out of the family home, causing the kids as little disruption as possible. On their ‘off’ days they stay in a shared, neutral bedsit. So while the parents live in the same spaces, they are never together, swapping from the bedsit to the family home on pre-arranged days.

JEROME’S STORY:

“It’s not easy, but it shows unity for the kids’ sake.”

Jerome in the family home

‘Splitting up when you have kids is tough. There’s heartbreak of course, and a sense of failure. Could I have done more to prevent it? Could she?

You don’t just lose your partner, there’s the whole future you took for granted, holidays and Christmases, hosting parties, and raising a family together. But after rows, tears and counselling sessions lead to the conclusion splitting is inevitable, putting your practical head on becomes a coping mechanism.

Separating two lives, melded together over nearly two decades, is no easy feat. If money wasn’t tight, it would be simplest to buy a second property. But who can afford to?

Sell the family home and buy two properties is the other option. But when you live in London, selling one four-bed home would only allow us to buy two flats with two bedrooms. If you have three kids of different sexes, it doesn’t really work – or seem fair – to make them bunk up all the time when they’re used to their own space.

Granted, it’s a first world problem, but this is how we are navigating our new, individual futures while still rubbing along amicably enough. Having a ‘nest based separation’ is a workable solution.

Susie found a bedsit advertised on Nextdoor, a local app, two minutes from the family home and the youngest’s primary school. It seemed sensible, and crucially, affordable (£600 pm including bills).

“The word ‘bedsit’ is a depressing one, it’s hard to imagine happiness, joy or success dwelling in one. But there are benefits.”

Simple but sparse, the bedsit is at least warm and comfortable

It’s in the attic of a nice family house – ours is local, cosy and warm. The owners respect our privacy and accept the ever-changing lodger.

There’s an ensuite, double bed, desk and kitchenette with a stove and microwave. I’ve got used to the ancient fridge’s hum as I fall asleep. Making coffee and lunch is fine, but eating dinner alone there? No thanks. I arrange to meet friends on those evenings.

I don’t really unpack, I live out of the suitcase for the week and use the washing machine at home. In the family house a cleaner comes once a week, but in the bedsit I make sure to hoover before swapping so Susie can’t complain I’m messy. I even bleach the loo, and I once tried to light a candle so it smelled nice for her. That backfired – she returned to it burning unattended and called it a fire hazard.

We agreed on Sunday evenings we’d attempt a family meal with the five of us. It’s not easy, but it shows unity for the kids’ sake.

Moving between two homes isn’t ideal, but the kids are relatively unfazed by the arrangement and I like the security of keeping the house. For now, this is good enough.’

The family settling down to their family meal on Sunday

SUSIE’S STORY:

“I lug my things upstairs, sit on a strange bed, and have a little sob.”

When she’s with her children, Susie feels life is normal

‘I was wheeling a vast suitcase out of our house, full of my clothes for the week, when I caught sight of the Dubai sticker from our last family holiday and I felt a stab of pain. Then a neighbour cheerily waved at me across the street and called over, “Off anywhere nice?”

I’ve lived on the road for 10 years, it’s where I’ve pushed buggies, traipsed thousands of school runs, and put out annual pumpkins and Christmas lights. Now, it’s the place where my long-term relationship crumbled.

On Sunday nights, I kiss the kids goodnight, and trundle into another family’s home, where I will lug my things upstairs, sit on a strange bed, and have a little sob.

I’ll change the sheets, hang my clothes in the tiny wardrobe, and light some scented candles.

”I have a framed picture of the kids smiling, and my daughter’s drawing which reads ‘Goodnight’ by the bed. I find it comforting. Jerome must too, as they remain unmoved.”

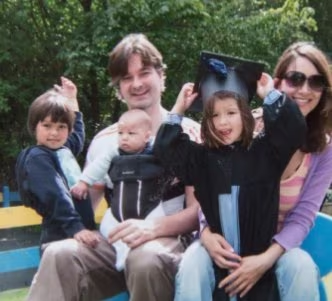

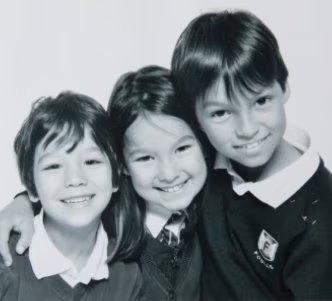

Left: Happier times when the family were together.

Right: The smiley photo that lives on the bedside table in the bedsit.

To make it feel more homely, I bought a large rug, while Jerome’s must-have purchase was the TV. Other than that nothing personal lives here. The room is clean, comfortable, and has wifi as we both work ‘from home’.

Seeing Jerome’s left-behind toiletries in the bathroom and favourite chocolate in the cupboard feels sad. He leaves milk in the little fridge, and a meal for one. He’s always been better at food shopping.

The kids never need to come here, that’s the benefit of nesting. They are settled at home and the inconvenience is only for the adults. But when the boiler broke in our family house, everyone piled over to use the bedsit shower. I worried they’d be upset by the rather alien little place, but they said, “Cool,” and loved climbing into bed to watch the TV (the room’s so small it’s the only place to watch it).

When I’m at home with the kids, life feels normal, as though Jerome is out playing football or with his mates. If the kids ask where Dad is, I’ll remind them he’s at the bedsit – but they’ll see him at ‘family dinner’. It was important to me we still shared a meal, but I know he struggles.

The bedsit is a step to a new, independent life. We didn’t officially ‘ban’ bringing other people back to it, but it would feel disrespectful to do so as we share the space.

We’re both open to dating, even tease each other about it, but we don’t pry. I doubt either of us will be ready for a committed relationship yet, but having a neutral place with the freedom to come and go makes dating an option. Under the same roof would have felt wrong.

When – if – one of us meets someone we’d want to introduce the kids to, the dynamics (and living arrangements) will change. We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.

It feels bizarre, (though not unpleasant!) not getting the kids up for school, and the time gives me headspace. But each week I am desperate to return to the home I nurtured over the years. Wheeling the suitcase back through the front door and hugging the kids when I return to them feels in every sense like coming home.’

Together alone: Distance makes the heart…

When Sille Krukow, a Nudge & Behavioural Design Expert, and TV editor/photographer Niels, married in August 2022, they had four children between them, aged from nine to 14, from previous relationships. Based in Denmark, despite now being husband and wife and very much in love, they have decided to stay living apart – 160km away from each other.

It’s an unusual arrangement for newly-weds still basking in the post-wedding glow, but it allows them both a better sense of self because their own spaces reflect who they really are, and can even make their relationship stronger.

NIELS’ STORY:

“Because we don’t live on top of each other, I have ‘me time’ but also, I really get to miss her.”

Niels stoking the fire in his home

‘One thing living apart has brought into my life is the phrase, “We’ll just make it work.” Together we always seem to – because we have to.

It’s very much a question of ‘mi casa es tu casa’ at both homes. We have each other’s keys, but we are different people and we have different habits and needs.

My kids live mostly with their mother. But so we didn’t have to sell our old family house, I found a lodge not too far away. And it’s a thing we have in Denmark called a kolonihave, which is basically an allotment with a small house, and you grow vegetables, like back in the ‘40s.

It seemed the best way for me to have a home close to the kids with them still able to have their own rooms and a garden. That would not have been the case with a two-bedroom apartment in the city.

“My house is actually made of straw – or to be precise, the walls of the house are hay bales that are stacked, sewn together, held in place by an iron grating and covered with mortar.”

Putting in the hay bales to insulate the walls of Niels’ kolonihave, and the end result once the mortar had been applied

Two builders and me, plus friends, helped to build the place. Sille joined in too so she knew what she was getting into – and she’s still here!

There are definite personal stamps on my property. I grew up with a fireplace at my parents’ house, and it was very important for me to have a fire. It helps me relax, which is something I share with my Danish father. I’m also half-Ghanian, and my mother always said, “In Ghana you always make dinner for an extra person if someone comes by.” So the living room, or where we eat, is the heart space of the house. It is small but we can squeeze 12 people round the table.

If you ask Sille, she’ll say I’ve got too much stuff. She went away on business recently and I’ve been clearing out the house to make it more spacious. But my whole life is there. I try not to be too much of a collector, and I’m downsizing a bit. I think I’ve done well but she will probably say, “This space does not work for me. We need to clean this up!” She would sweep everything straight into a box, but I am more attentive to details and like putting things where I think they belong.

Niels enjoys displaying his belongings, and taking time to decide on the right place for each item

We really don’t argue about the small things that are of no consequence. You could make a documentary about stacking a dishwasher – the way guys do it and the way girls do it – but there isn’t a right or a wrong way. I have the way I do it, but it’s a process to be open to the way Sille does stuff too. That might not be the case if we lived together 24/7.

Sille should always feel at home in my house, and I want her to be involved and make decisions about how it looks, so she can paint the bathroom ceiling if she wants. It’s a give and take relationship based on respect.

I used to think I was impulsive, but living the way we do has taught me that I’m not. I plan ahead so I shop for Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and I know I’m going to cook this, this, and this. At Sille’s house you can just pick any food out of the cupboard without asking because she rarely has a plan for what will be used on that day.

The most important thing for me is because we don’t live on top of each other, I have ‘me time’ but also, I really get to miss her.

We’re good at saying when we don’t think we’ve been seeing each other enough. It’s great when we can get our calendars together. We try to be flexible, and I’m happy to get up at 5.30am and jump on a train to get back to my job.

I think we’re doing alright. Yes, we just make it work.’

SILLE’S STORY:

“We’ve never had everyday life as a couple, and that’s quite weird when you’re married”

Even when they are apart, Sille and Niels speak four or five times a day

‘I grew up in a communal house with a lot of people and never had a super big attachment to stuff like furniture. After my divorce I left everything for my ex-husband, so I didn’t have many belongings, not even a TV, but I wanted a base for the kids to call their own. Even though Niels and I were together, a year ago I bought an apartment in the district of Frederiksberg in Copenhagen, near the zoo.

Once it was obvious things were getting serious, we still wanted the kids to feel like they had their own homes. We were very conscious about that, before we decided how to go about living and merging everything – and everyone – together.

We spent a lot of time travelling together and visiting with the kids, putting a great deal of effort into making sure they didn’t feel forced to be comfortable with each other. They didn’t ask for extra siblings. It has to happen organically, not just because their mum and dad want to be together. And it worked, now they call each other ‘bonus siblings’.

When I’m travelling abroad and missing home, home is where the kids are – and that could be at mine, but also at Niels’ house. They’ll go there to hang out and watch a movie.

When Niels was building his straw house in Odense he would ask my opinion about certain things, but it wasn’t my home that he was building, and my home was not his home either.

Wherever we are – and we both have busy lives – we speak four or five times a day. And, if I am not travelling, try to see each other two or three times a week. We make sure we have a family weekend when everybody gets together at least once a month. And as a couple we plan getaway weekends as a special thing. Denmark is a small country and Niels is only a couple of hours away. It’s 160km, but I could go over today if a meeting got cancelled. And it works the other way too.

Niels & Sille togther in Sille’s home

“We prioritise our time together and make a conscious effort to take care of our connection and love – after five years we are still very much in love and miss each other all the time.”

He has a drawer of his stuff here, and I have a couple of drawers at his house – he thinks I have more space than him! But we are different people, used to doing things in different ways. We don’t argue about day-to-day things that annoy other couples such as replacing the toilet paper. Although he doesn’t like me tidying away his stuff, I’ve found little corners I can tidy without him really noticing…

We do argue once in a while, but because we have somewhere else to go, we make a bigger effort to get back together. We never take each other for granted. I also have to look at myself and take on board whatever might have been my responsibility. And that is only possible when you have time and a place of your own to reflect.

The most important space for us in both our homes is actually the common area – the space where everybody hangs out when we have friends over. Niels built his house along those lines and I knocked walls down in my apartment for just that reason.

But the thing that’s missing sometimes is not actually having time with just the two of us.

It’s a funny thing that we actually don’t know how each other behaves when we just chill and no one else is around. I’ve no idea what Niels does when he relaxes. We’ve never had everyday life as a couple, and that’s quite weird when you’re married. At the moment the set-up works for the six people involved but once we get to the stage where the children have moved out and there is only the two of us, we have a dream of having a place in nature and building our own house.

That is when we will get to do things together, and share experiences, just like other couples.’

While very much in love, the couple don’t share an approach to interior design

Regardless of what friends and family say – and both of these couples were told their lifestyle choices “would never work” – feeling at home in your own space to engender a sense of identity and belonging, whatever your circumstances, is always more important than what anybody else thinks. Never mind the norm. Just do what works for you.

Words: Susanna Galton and Bill Borrows

Photography: Teri Pengilley and Sophie Kalckar