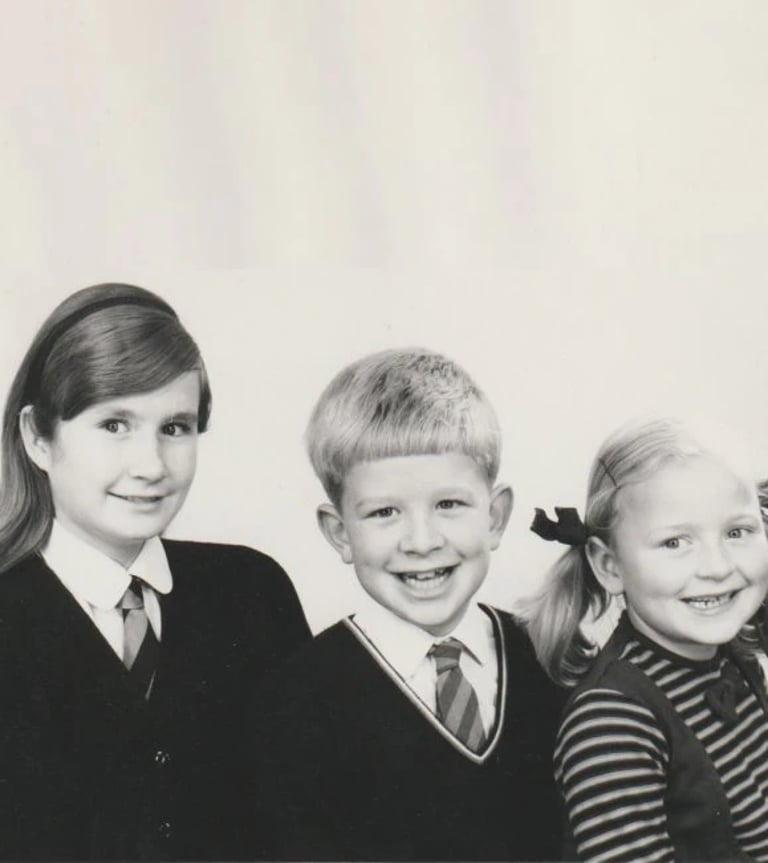

Christina Patterson, whose brother Tom died unexpectedly aged only 57

The night my brother died, I slept in his spare room. I lay on the bed next to my father’s old desk, and the leather chair with the brass studs, and the lamp with the embroidered shade my mother inherited from her mother, and listened to the hammering of my heart.

Just hours before, Tom had been on the phone to our aunt. She called me to say that the line had suddenly gone dead. I was on the motorway, on the way to his house, when I got a call to say that the ambulance had arrived too late.

It happens to us all, this moment when someone we love is chatting on the phone, or stretched out on the sofa gulping tea from their favourite mug, and then, suddenly, they are not. If we – and they – are lucky, it happens after a long, happy life. If we – and they – are not, it doesn’t.

My sister, Caroline, was 41 when she collapsed while she was washing up. My brother was 57 when his phone call ended so abruptly. When it happens, we who are left are parachuted into a whole new world of grief, shock and disbelief. We are also shot into a world of draining drudgery and paperwork.

When our mother died, it was Tom who did most of the clearing and sorting out. He lived nearer than I did to the 1960s red-brick box that had been our family home for 52 years. I was relieved when he said he wanted to do it.

“I gasped when I found my mother’s navy handbag in one of his cupboards. It still had her purse in it, and the lipstick she always wore.”

In the months that followed, he would summon me to go through boxes he had found in the loft. In one, I found piles of my school exercise books, filled out in neat pencil. In another, I found paintings and collages I’d done of Roman soldiers and the six wives of Henry VIII. As I gazed at them, I had a flash of the joy I used to feel as I sat on my bedroom floor surrounded by sequins, crayons and sheets of coloured paper.

Did I take them? Of course I didn’t. My flat is already full of stuff and I don’t have an attic or cellar. In the end, I didn’t take much: a small painted cabinet, some plates my parents had when they lived in Bangkok, a few vases, a few ornaments, a few paintings. My brother took much more, but then he had a three-bedroom house with a loft and a garage.

This time, it was different. Oh my God, it was different. Tom didn’t have a partner or children. He had filled his house with family mementos and there was only one person who could clear them out.

If you have done this task, you will know what it’s like: to clear up the dishes that the person you loved never got to finish washing up, to open cupboards and find the coffee cups your mother used to lay out on a tray with a plate of little cakes, to see the casserole dish she used for her beef stroganoff, which is now your beef stroganoff and perhaps your brother’s beef stroganoff, though you never got to ask him if he kept the recipe and tried it.

You will know what it’s like to take a deep breath, as if you are gulping for air, and then open a drawer or wardrobe and find the shirts or socks your brother or husband or father wore until just a few days ago. You will know what it’s like to touch the fabric and know it will never touch their skin again.

That’s the worst thing: the clothes. And the flannels and the toothbrushes and the razor blades and the combs and the half-finished bottles of shampoo. I got some bin bags and stuffed it all in them. There were other things I took to charity shops, but not the clothes. I didn’t want to see or touch the clothes again.

“When I saw the tiny apron with the little red donkey, I had to clamp my jaws together. I thought it would be upsetting for Tom’s neighbours to hear me howl.”

After that, it was like an archaeological dig. It wasn’t just the cupboards and the drawers. It was the boxes. Tom’s garage was full of boxes. In one, I found the scout uniform he wore when he was 11, the Chelsea football scarf he knitted, a tiny apron with a picture of a little red donkey. As soon as I saw it, I remembered the cine film my father took, of Tom as a toddler playing in a sandpit with Caroline. He was wearing a pink overall and the little apron. When I saw the donkey, I had to clamp my jaws together. I thought it would be upsetting for Tom’s neighbours to hear me howl.

I gasped when I found my mother’s navy handbag in one of his cupboards. It still had her purse in it, and the lipstick she always wore. I gasped again when I found a sword. It was the sword my father was given when he joined the diplomatic service, with a gold tassel and a royal crest. I didn’t know what to do with it. I still don’t know what to do with it, and have hidden it in my wardrobe, behind my summer dresses.

My brother’s house was like the museum of my family. As well as the objects, pictures and ornaments from our family home, there were my father’s photo albums and diaries and letters and papers, and my mother’s photo albums and diaries and letters and papers, and Caroline’s and, of course, Tom’s. For months, I sifted through it. I threw out quite a lot and used what was left to write a book that told my family’s story. That process, of assembling and sifting and reading and writing, felt like a kind of catharsis that was part of what helped me keep going.

In the end, I took some pictures, a rug, some silver ornaments from Bangkok, some of the blue and white ceramics my mother collected and loved. I took my father’s gold-embossed Shakespeare. I took my sister’s books about the Russian royal family. And I took my brother’s LPs. I still can’t listen to them. I kept them because he loved them and because one day I want to listen again to the soul-thrilling, heart-kicking rhythms of Motown he would blast out as he sank on the sofa and poured himself a glass of red wine.

I didn’t want to be there when the house clearers came. I didn’t want to see my family’s stuff packed into a van to be thrown away. But I didn’t need it, and I didn’t have space for it. I just wanted a few things that brought back happy memories. I kept the leather chair with the studs because it reminds me of my father writing Christmas cards as he listened to Bach. I kept the lamp with the embroidered shade because it’s elegant, like my mother, and it reminds me that even the love of those we have lost is a light that stays on.

Christina Patterson’s family memoir, Outside, the Sky is Blue, is published by Tinder Press

Illustration: Lydia Blagden

Photos: Christina Patterson