Mark Pagán, the creator and host of the podcast Other Men Need Help, says exchanges about mental wellbeing happen “between the cracks” as “quiet negotiations” in the interactions men have with each other. His example would be a stereotypical conversation about sport, where two friends talking about game-play analysis would also contain mini-dialogues about a cancer diagnosis, romantic relationships, or issues with a job.

“When asked to sit stationary and talk openly about their best friends, the men I met tended to fidget with an object within reach.”

For his podcast, Mark has been seeking to get to the bottom of male friendship. Surprisingly, he has discovered that the bonds of friendships are visible in plain sight in our homes.

In 2020, I was living in a New York City apartment, maybe larger than average, shared with my girlfriend Caitlin and a recently acquired pet pigeon named Valentina (which is truly an absurd story for another time). When the world felt more open, the 800 square feet (75 square metres) of the apartment felt like an oasis of sorts, more than enough room for our lives to be private or connected after hours outside of our walls.

I was also deep into editing the third season of Other Men Need Help. The podcast, which I host and produce, looks at the way men present themselves to the world and asks them to share what’s underneath – most often reflected in stories framing their insecurities and various pursuits to build connection with others.

Our third season, set to examine friendships between men, had me travelling all over the US, exploring the interior lives of our interviewees. So if there was a question of whether signs of friendship existed in the homes of men, the answer was yes, it certainly does.

Instead, the question should be: how (physically) does it exist in the home? How does someone exist in our spaces without being there? Having spent over 100 hours sitting in the kitchens, offices, and living rooms of men’s homes and asking them question after question about their closest friendships prompted a few insights about men’s interior lives (and the interior spaces where those lives took place). Notably, two patterns emerged.

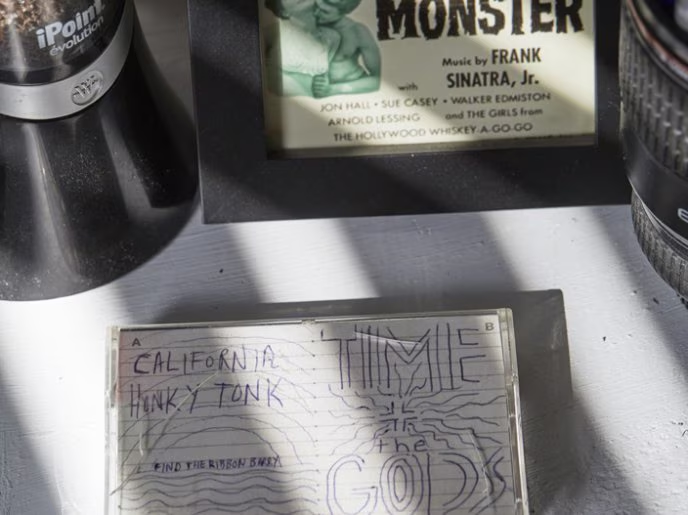

A 20-year-old mix tape from Isaac, resting in Mark’s office

Objects of emotion

When asked to sit stationary and talk openly about their best friends, the men I met tended to fidget with an object within reach. When I asked Kyle why he wouldn’t ask Javier, his best friend, to listen to his emotional needs, he slid his iPhone under his hands and began tapping. When Lars started talking about how his friend Neil wouldn’t invite him to do certain activities, he took the salt and pepper shakers sitting in front of him and moved them around like bumper cars.

Even when I wasn’t even prying for information, the bonds between objects and friends were all over the place. With our increasingly super-duper digital world, where memories exist on phones, computers, and social media platforms, I was moved to see that people still hold onto the printed photos and ephemera from nights on the town with the boys that archive our relationships with some of our nearest and dearest.

From Polaroid hugs resting under magnets on a refrigerator door to an inside joke written on a cocktail napkin, the mementos of male friendship were part of the accents of any man’s home.

My favourite moment came in Tim’s home, when I pulled a copy of The Sopranos Sessions off his bookshelf, literally out of genuine interest as a potential read. He smiled and said, “Yeah, that was a gift from this guy”, pointing to his best friend Logan (one of the few times we interviewed two friends at home).

To absent (guy) friends

We had about 90% of the season ‘in the can’ by the time we all began having to stay inside, quarantined with those we shared our homes with. Caitlin and Valentina the pigeon were lovely company for the most part. But after a month together all day, every day, I was desperate for my former outside connections.

I missed my friends. I missed my guy friends. I needed a respite from discussing everything with my domestic partner. For me, that respite was Isaac.

Isaac and I had known each other since we were teenagers. I don’t want to expose our ages here, but I can say it’s been a decades-long friendship. We’ve seen each other through potentially questionable choices in fashion, romantic partners, and music (we both had a Steely Dan era). He’s one of the closest, longest-lasting, and dearest people in my life.

Tuesday night movie club

It started with the prompt to get on the phone. It had been a while, and Isaac suggested a catch-up call. During our chat, I must’ve mentioned the mountains of movies I was watching in the midst of Other Men Need Help editing sessions. As a dad at home with a toddler, his intake of movies that didn’t involve some kind of animated singing train was limited.

“I too would like to watch a lot of movies made for adults, Mark.” His suggestion: “Let’s watch a movie a week and talk about it”, which, reading between the lines translated to “PLEASE, GIVE ME SOMETHING ELSE TO WATCH. I’M BEGGING YOU.”

So together we made an effort to watch something meant for adults. Roughly, every Tuesday around 7pm, we got on the phone, talked about what we had seen the previous week and ended each call with what our next viewing would be. It started with Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Sandwiched in these 90-minute calls came life updates: from the mundane (“some guy on our street walks around playing songs from Rocky IV”) to the existential (Isaac’s mother’s battle with cancer; the threat of viral infection).

Over months, we made our way through everything from What’s Up, Doc to Bacurau to Cats. And I, a masculinities investigator, began noticing a pattern. Or rather, my own pattern.

The fridge door, housing a collection of magnets, postcards, and most importantly, photos of friends

Exploring the emotional landscape of the home

During these movie discussions, I would often wander around the bedroom, arranging the socks and clothes on the floor needing a place to hide. As we moved into discussions about our romantic partners, I’d rearrange the office. A typically organised space, I’d slightly adjust the angle of tchotchkes [decorative bric-a-brac or ornament] on shelves, a future reminder of Isaac’s celebratory words about his wife’s career steps.

Sometimes when having a difficult time describing my relationship frustrations, I’d run a finger across speaker dust, leaving a trail of thought ellipses, a fingerprint reminder of reflection to complete by our next call. When our talks would reach a sober point, reflecting on politics, the pandemic, and ageing parents, I’d frequently sit in the wooden chair at a farm table I bought in 2013 that the pandemic had appropriated as my desk.

Something about the stiffness encouraged deeper attention. To be honest, I sometimes wouldn’t know what to say, my words stuck somewhere in between my heart and my larynx. When that would happen, I’d pick up pencils and move them around like they were bumper cars.

I, too, had found my fidget. When adding my own patterns in with the bouillabaisse of discoveries from two years of reporting, I have a bit more fondness for the unconscious actions we as men exhibit when confronted with the emotional landscape in our deepest friendships.

I don’t view these actions as fidgets anymore. Like the Polaroids and gifted Sopranos books we keep in our homes, I view the fidget as physical punctuation of sorts. A punctuation on the deep bonds our friendships that rest in our bodies and the spaces we inhabit.

Ultimately, my calls with Isaac tapered off as the world began opening up again. My girlfriend, pigeon, and all our stuff moved to a new apartment – a process that still provides discoveries (which is a nice ribbon to put on the Sisyphean task of finding space for your stuff in a now slightly smaller New York City apartment).

The tchotchkes are unpacked and in new places. The speakers are upright and dusted, the marks of earlier conversations in an earlier home removed. In an old shoebox, I discovered an old picture of Isaac and me. It’s currently resting on my desk, waiting for display. I’m just not sure where to put it yet.

Note: Some names have been changed. Photos by Jurate Veceraite

Download the Life at Home Magazine